Last week I posted a blog on Francis Greenaway on the Ten Dollars Australian banknote. This the follow up blog to complete a very strange story regarding the two men whose faces grace the ten dollar bank-note.

If you would flip the note over then you will find the subject behind this months story. A writer of bush ballads, a politically motivated man, a drinker, a womanizer, a bankrupt, a romantic, a larrikin in the true sense of the word. Henry Lawson was all this and more. Interesting to note that this banknote not only has a convicted forger on one side but a bankrupt alcoholic on the other. Only in Australia! There is just no escaping that convict streak it would seem. His story is quintessentially Australian and his demise a sad reflection on the times he lived in. Possibly his isolation in deafness had much to do with his alcoholism but although he might never hear music in his adult years, his words were music for many others who loved his works.

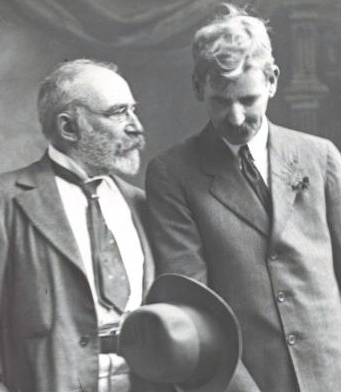

Henry Hertzberg Lawson was the son of a Norwegian sailor named, Niels Larsen. He was born among the rough and ready goldfields of Grenfell, New South Wales on the 17th June 1867. His father working as a gold miner, changed his name to a more Anglicised one and called himself, Peter Lawson. His mother Louisa was to have a profound influence on him throughout his life due to her feminist leanings. She took a significant part in women’s movements and was additionally an editor on a women’s paper called “Dawn”. Using her literary connections she was also responsible for the publishing of her sons first volume of works.

Henry began his schooling at the age of nine in Eurunderee until moving on to attend the Catholic school at Mudgee. He was known to be a very shy young lad and his problems were exacerbated by an ear infection that left him totally deaf by the age of 14. Most of his education was therefore achieved by means of reading as classroom interaction was extremely difficult for him. He left school early and his first official job was as an apprentice railway coach painter in 1887. After his parents separation he moved to Sydney to live with his mother who had bought a newspaper and it was via this medium that he published his first pieces. Henry’s poem, “His Father’s Mate”, was also published in the Bulletin that same year 1888. He worked during the day and studied at night in the hope of finishing his senior school and being accepted for a university education. In the 4 years that followed he published some of his most notable works, “Andy’s Gone with Cattle”, “The Roaring Days” and ‘The Drover’s Wife”.

For a while he worked in New Zealand as a shearer and had a reasonably successful time there and seemed for the most part to be untroubled by the bouts of alcoholism that he often suffered when living in Australia. Later, Lawson and Bertha, his wife, along with their 2 infant children went to live at Mangamaunu near Kaikoura, in the South Island. There they worked as school teachers at a Maori school. They did return to Australia in 1898 but Henry’s return to drinking and problems within his family and a lack of recognition for his published works left him disenchanted with life there. In 1900 with the help of his publisher and the Earl Beauchamp from the New South Wales government he raised enough money to venture to England. In the 2 years he was there Lawson produced some of his best works but yet again the demons of alcohol and financial poverty forced his return to Australia. His health at this point was on a downturn and the road ahead more difficult than ever before.

Upon their return to New South Wales Lawson became increasingly problematic and this saw the end of his marriage to Bertha who took the 2 children and moved in with her mother. After failing to pay maintenance to her she had a summons issued against him and a magistrate ordered that he pay 2 pounds weekly toward their upkeep. To add to his problems his mother had become mentally ill as well after the collapse of her newspaper, “Dawn”, and she was to end up dying in an institute for the insane in 1920. In the five years following 1905, Lawson was constantly being arrested and charged either for inebriation or non-payment of maintenance. On one visit to “His Majesties Hotel” better known as Darlinghurst Gaol he wrote a memorable poem, “One Hundred and Three”, which was also his prison number. In this poem he refers to the gaol as “Starvinghurst Gaol”, due to the paltry rations of food they all received there as inmates. He even turned to street begging as a way of funding his drinking. Three of his best friends banded together and set him back on his feet, financially, once again. A tremendous gesture of faith and solidarity on their behalf in this man whose written works inspired them.

He was eventually befriended by a lady 20 years his junior called, Isabel Byers and she was to provide him with food and shelter on a great many occasions over the coming years. She believed he was Australia’s greatest living poet and by taking care of him she intended that he should keep writing. When the First World war broke out he was working again providing results for the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area. During the war years he continued to write and in general was successful with public reviews of his pieces. In 1921 Lawson was struck down with a stroke. His health was not so badly affected that he could no longer write and for a short while he did so. The stroke however would have the last say and he died peacefully in his sleep from a cerebral hemorrhage on September 2nd ,1922. A state funeral was also provided on the grounds of his having been a ‘distinguished citizen, as by then his stature as a writer had grown considerably and his works were too numerous to be ignored. He was the first writer in Australian history be given this honor. The mental pictures he painted with his words of this era of our young Australian nation were poignant and in many ways harsh yet he still endeared himself to a nation. He always displayed an indomitable spirit which was a sign of a true Australian. Plainly said, he never gave up hope. His written words have earned him his place in history and his place on the ten dollars banknote. I cannot possibly imagine how he would have felt about this given his life of poverty and indebtedness.

He remains to this day one of my favorite Australian poets and I too am inspired by his perseverance and commitment to his art.

A list of a variety of his works include:

“A Child in the Dark, and a Foreign Father” (short story, 1902)

“A Neglected History” (essay)

“Andy’s Gone with Cattle” (poem)

“Australian Loyalty” (essay, 1887)

“Freedom on the Wallaby” (poem, 1891)

“Saint Peter” (poem, 1893)

“Scots of the Riverina” (poem, 1917)

“Steelman’s Pupil” (short story)

“The Babies of Walloon (poem, 1891)

“The Bush Undertaker” (short story, 1892)

“The City Bushman” (poem, 1892)

“The Drover’s Wife” (short story, 1892)

“The Geological Spieler” (short story, 1896)

“The Iron-Bark Chip” (short story, 1900)

“The Loaded Dog” (short story, 1901)

“The Teams” (poem, 1896)

“The Union Buries Its Dead” (short story, 1893)

“Triangles of Life, and other stories” (short stories, 1916)

“United Division” (essay, 1888)

“Up The Country” (poem, 1892)